Product Alignment? It sounds like corporate jargon, and it is. In short, product alignment is the way that products are presented in the best possible light to different target audiences. In the case of Gibson guitars, a very different customer will buy an entry level solid body to a high-end carved-top jazz box, and only the biggest retailers would benefit from stocking the entire range. Gibsons have always been exclusive products, and the number of dealerships in an area has always been limited. But, with any fine product, there will always be a demand from dealers wishing to stock them, and from consumers who want a slightly more affordable version. A balance must be drawn between exclusivity, brand reputation and supplying this demand. Gibson's parent companies CMI and Norlin, and indeed todays owners, all dealt with this issue in a similar way over the years, primarily launching non-Gibson branded 'Gibsons'. The most obvious examples are the Japanese, Chinese, and Korean Epiphone Gibson copies, produced since 1970. But very many non-Gibson Gibsons were also built at the companies American plants over the years. This article takes a look at some of these American Gibson offshoots, and the changing face of Gibson product alignment in the CMI and Norlin periods.

Gibson first started producing a second brand of acoustic guitars in the 1930s, named Kalamazoo, after the home town of Gibson. These were rather nice instruments, not quite as fancy as those branded Gibson, but still some very nice guitars. Production ceased with the outbreak of World War 2.

As the 1950s dawned, electric guitars were slowly gaining popularity, increasing year on year with their continued use in popular music. Another major expansion in it's dealership networks came in the late 1950s, when then-owner CMI bought the Epiphone brand. By late 1958 Epiphone guitars were being built at the Gibson Kalamazoo plant, using much of the same materials and components as the Gibson models - but because they were distributed through an alternative network of dealers, CMI was able to massively increase the reach of it's Kalamazoo-built guitars, without upsetting existing dealers too much..

But Kalamazoo-built Epiphone guitars were of similar quality to Gibsons; not really aimed at a different market segment. As the 1960s wore on, cheaper solid bodies built in the US and imported from Asia were outcompeting Gibson on price, and although nowhere near a Gibson in quality, they were certainly getting better. So to increase market share, and tap into the ever growing ranks of young musicians, CMI resurrected it's 1930s Kalamazoo marque, taking the latest technology in man-made wood materials, and added a large pinch of Leo Fenders rationale in construction. The KG guitar and KB bass series sold very well. Although built in Kalamazoo, assembly of these guitars did not require the skilled workforce at the main Parson's Street plant, so production was based at plant II, 416 E. Ransom Street. It was still a US-built guitar, with Gibson hardware, but at a much-reduced cost. In late 1966 the entry level KG-1 cost $89.50, compared to $149.50 for the cheapest single pickup Gibson Melody Maker.

But as cheap Asian guitars improved in quality, and financial pressures continued to mount on American manufacturing, budget US brands like Kay and Harmony simply could not compete. Epiphone production was moved to Japan in 1969; it was no longer a marque on par with Gibson, but one aimed strictly at the lower end of the market, and hence replaced the Kalamazoo models.

The 1970s were a difficult time for a lot of American manufacturers, but there was sufficient demand for Gibson products that the Kalamazoo factory could not fill. A new plant in Nashville Tennesee was opened in 1974, but ironically this left Gibson with too much capacity, and the company failed to turn a profit from 1975 onwards. So Gibson had the factories and the workforce, and there was plenty of demand for entry and mid-level guitars. Just as it did with the Kalamazoo brand 15 years earlier, Gibson would take the latest developments in composite wood technology add a bolt-on neck and brand it with a name that eluded to it's heritage, whilst keeping it separated somewhat from the high end products that were truly Gibson.

In June 1980 Gibson released a newsletter entitled 'Gibson News', describing, amongst other things, new dealer authorisation plans for the Autumn of that year. In short, Gibson were to authorize it's main product line (it's Professional series) separately from it's acoustics, and again separately from a new range of entry/mid level instruments: the sonex series. This is NOT to be confused with the Sonex-180 guitars themselves - although they were in the series, later to be joined by the GGC 700. This meant certain dealers would get to sell Gibson's entire line, whilst others would only get to stock acoustics, or models from the sonex series.

Then there was the Firebrand series. Again not to be confused with the existing models with 'Firebrand' in their name, The "Paul" Firebrand and the The "SG" Firebrand, although, again these models were now included in the series, and were renamed The "Paul" Deluxe and The "SG" Deluxe.

The 1980 newsletter went on to explain in great detail about the three series, identifying characteristics of each: see table, left. Within each series any model could potentially have three instruments.

"it is possible for Gibson to introduce instruments which follow the good, better, best concept (triadic alignment) or Deluxe, Standard, Custom models. For example, theoretically, Gibson could introduce one instrument with nine possible models"

| Professional | Custom | no entry |

| Standard | no entry | |

| Deluxe | 335-S Deluxe | |

| Firebrand | Custom | 335-S Custom |

| Standard | 335-S Standard | |

| Deluxe | no entry | |

| Sonex | Custom | no entry |

| Standard | no entry | |

| Deluxe | no entry |

There were a number of guitars produced in late 1980/early 1981 that seem to defy Gibson's usual naming conventions, and this system of classification is behind each of these. So let's look at a couple examples. Firstly the newly introduced 335S; the high end model is the Deluxe rather than the expected Custom. As can be seen on the right, this relates to the fact that the Deluxe is in the Professional series, whilst the Custom and Standard are Firebrands. Should a 335S Professional Custom be launched, it would become the top 335S model.

How about the Les Paul? In the price list immediately following the product alignment announcement there were five Les Paul models in the Professional series, and, whilst not actually named 'Les Pauls', two in the Firebrand series. Already the 'triadic alignment' concept is breaking down. There is no way Gibson were going to call the Sonex guitars Les Pauls, but they were effectively the Les Paul's sonex series entry.

| Professional | Les Paul Artist | |

| Les Paul Artisan | ||

| Custom | Les Paul Custom | |

| Standard | Les Paul Standard | |

| Deluxe | Les Paul Deluxe | |

| Firebrand | Custom | no entry |

| Standard | The "Paul" Standard (previously The "Paul") | |

| Deluxe | The "Paul" Deluxe (previously The "Paul" Firebrand) | |

| Sonex | Custom | Sonex-180 Custom |

| Standard | Sonex-180 Standard | |

| Deluxe | Sonex-180 Deluxe |

1982 Sonex-180 Deluxe A few Sonex guitars made in mid 1982 were branded 'Sonex by Gibson' more

1982 Sonex-180 Deluxe A few Sonex guitars made in mid 1982 were branded 'Sonex by Gibson' moreMoving on a year or so, and new models were being introduced, that don't adhere to the definitions of 'series' and the 'triadic alignment' suggested a year earlier. Whilst the idea of a separately authorised (ie available to more dealers) sonex series holds throughout the rest of Norlin's ownership of Gibson, the details are quickly forgotten. By April 1981's price list, the Firebrand series is gone, with the The "Paul" Deluxe moved to the Les Paul segment. And by the end of '81 Gibson had added two new models to the Sonex series, and whilst both have the 'Gibson Guitar Co.' branding, neither completely conforms with the chacteristics that define the series (above): the GGC 700 has a mahogany (rather than resonwood) body and Sonex Artist is priced at $799, way above the $450 sugested limit.

Although the changes described above were clearly planned at length, they were perhaps too complicated for full implementation, but they do explain a number of anachronisms: why the 335S Deluxe is a finer model than the 335S Custom, why The "Paul" and The "Paul" Firebrand were renamed The "Paul" Standard and Deluxe, and why the GGC 700 was part of the Sonex series, despite having a mahogany rather than resonwood body.

1983 Epiphone USA price list

1983 Epiphone USA price listAround the middle of 1982, Norlin decided to build Epiphone solid bodies back in Kalamazoo, (although production soon moved to Nasville) and brand them Epiphone USA. These guitars were additional to the Japanese Epiphone semi-acoustics still in production. Initially there were two models, the Spirit and Special, both first demonstrated at the Atlanta NAMM show, and shipped towards the end of the year. These were rather nice set neck models based on the Les Paul Double cutaway and the SG respectively. As the Fall 1982 issue of Gibson Gazette states: "We are proud to be championing a new trend back to American labor by offering the player a high quality professional instrument at a cost competetive with the foreign imports". These were actually really nice guitars, and very well priced. The entry level (single pickup) Spirit I had a list price of just $399 - placed around the same price point as the Sonex-180 Deluxe. The top of the range Spirit had twin pickups, a bound body and neck, and a very nice curly maple top. this was $624.99. About the same as the old (Firebrand) The "Paul" Deluxe.

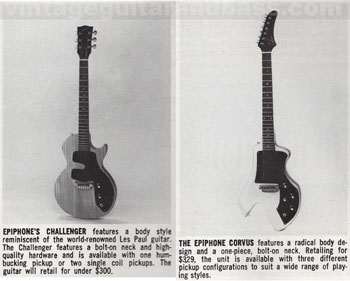

1983 Epiphone USA Challeger and Corvus

1983 Epiphone USA Challeger and CorvusAs 1983 dawned two new entry level models with bolt-on necks were added, the Challenger and Corvus, first shown at the NAMM winter market, January 1983. But as quickly as it arrived, Epiphone USA was gone. None of these guitars were deleted however, all were simply rebranded Gibson, and moved from the Epiphone price list (January 1983) to the equivalent Gibson list (June 1983) with no significant change in price.

$1699

$125

$3450

$700

$4700

$3495

$6999

$370

$995

$950

$3800

$5000

£5270

£2398

£2450

£900

€799

€350

€2895

€2798